Eavesdropping on the Bolsheviks in Surrey

As a student of political economy, I ought to have found the onset of the pandemic fascinating: the effort to find a pause button for a capitalism built to spool endlessly into the future, the contortions of discourses and institutions shaped for decades to uphold the now exploded fiction that economic misfortune only afflicts the unproductive or otherwise undeserving, the spreading realisation, as central banks extend massive new credit everywhere, that there’s been a magic money tree all along. But after a couple of weeks, I couldn’t bear the gap between what was and what ought to be any longer, and fled to the 1920s, where I soon found myself eavesdropping on the Bolsheviks.

My 1920s, which I started visiting at university, have always been Moscow-centric. In 1986, just before the Cold War that had pervaded my childhood was to evaporate, historians’ debates on the Soviet 1920s seemed to have high political stakes. Were Stalin and his slaughter of millions an inevitable result of the Bolshevik ideology, suggesting that the most one could expect from the CPSU was a milder form of totalitarianism in which the camps and secret police had been retooled as instruments of repression rather than mass murder? Or did Stalin simply manage to politically outmanoeuvre advocates of alternative policies no less authentically derived from the Bolshevik tradition, but closer to the emancipatory ambitions of socialism, an enduring alternative that might allow the USSR to shake off the Stalinist legacy and embrace thoroughgoing reform? It was scant months before the increasingly evident radicalism of Gorbachev’s perestroika and glasnost was to consign these questions to irrelevance, and scant years before the USSR and all versions of the Bolshevik project lay on history’s ash-heap.

Thirty years on, my visits to the Soviet 1920s take place in a very different intellectual and physical landscape. Lockdown has meant a lot of walking in the woods of Surrey with Ziggy, my maddeningly indefatigable young dog, who has effectively avenged Pavlov’s depredations against his kind by conditioning me to cater to his every whim. Carrying the 1920s with me eases the burden of my service to the four-legged tyrant. The Soviet archives have yielded many transcripts of crucial policy meetings, recorded by hard-working stenographers for a posterity now arrived. So as Ziggy roams among the trees in search of new smells and coprophagic delicacies, I eavesdrop on Bolshevik policymakers decades dead. This is possible thanks to ‘Milena’, a Russian cousin of the affectless computer-generated voice that talks to you when you call the bank. Milena gives what must be confessed a lacklustre performance of the words of Stalin and his comrades, but the discussions themselves are riveting. What I’m listening to are debates on monetary policy. By late 1922, still suffering through a massive famine, after years of relying on money issue to finance government, the Soviets were finding it hard to print money faster than it would lose value — a value measured with difficulty by some of the world’s most accomplished practitioners of the nascent arts of macroeconomic statistics. In the early 1920s the Bolsheviks were arguably more clear-eyed about the nature of hyperinflation and what it would take to steer out of it than policymakers in Weimar Germany. (This seems to have been the impression of Keynes, who also frequently joins me in the woods, voiced by my phone with an incongruous American accent.)

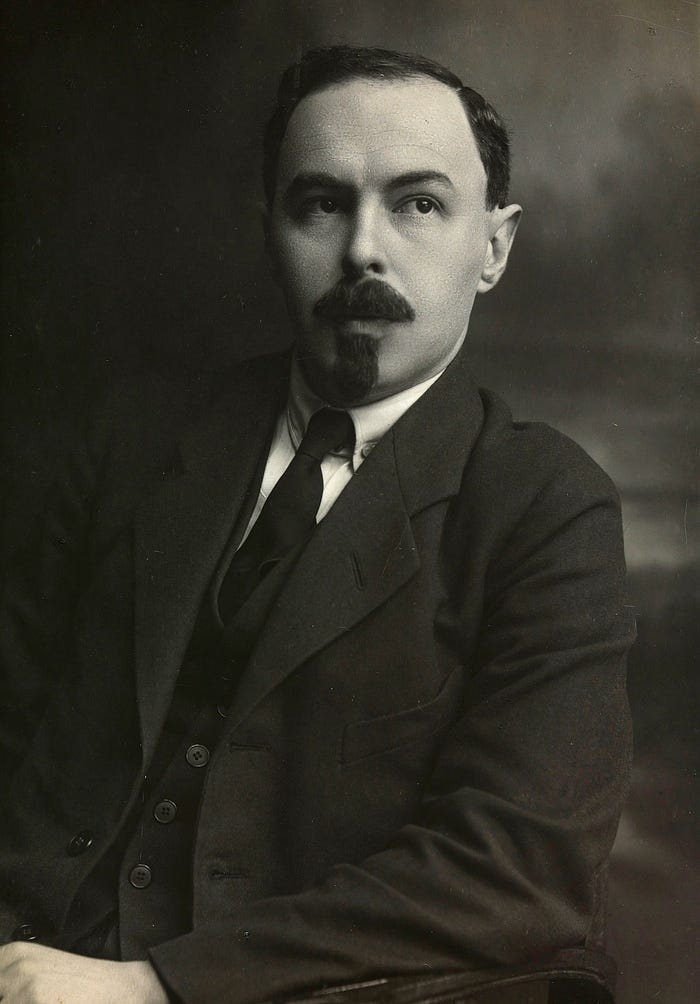

The protagonist of the Soviet effort to deal with hyperinflation was Grigorii Sokolnikov, the People’s Commissar of Finance from 1922 to 1926. Sokolnikov and I first met some 25 years ago, when I wrote a chapter on the origins of the Soviet monetary system as background to a study of how it collapsed and what ensued. But I’m coming to know him much better now than I did in my callow scholarly youth. It’s hard not to be impressed with his drive and initiative, as when, in late 1922, he successfully sought Stalin’s intercession (at 1130 pm!) to block newspaper publication of a price index pushed by some bureaucratic rivals. His signature tactic was exuberantly sarcastic incineration of straw versions of his adversaries‘ arguments, allowing him to stride triumphantly from the ashes in possession of the sole policy both authentically Marxist and practically sensible. Given that his monetary prescriptions were drawn from the classic capitalist arsenal — he had studied economics at the Sorbonne before travelling back to Petrograd with Lenin in the notorious sealed train carriage — claiming both virtues was more than a little audacious.

Milena’s antiseptic rendering can make it hard to tell when Sokolnikov is joking. But he still makes me laugh. I assume he was trying to be witty rather than informative in explaining to his colleagues that the Soviets couldn’t emulate Napoleon in basing a restored monetary system on plundered gold, insofar as the Red Army couldn’t reach London or New York without a navy, the acquisition of which would itself require exorbitant gold outlays. The monetary reform he initiated was less bold than a transatlantic raid, but bold nonetheless: for a transitionary period, Soviet Russia would have two currencies. The existing ‘payment token’, known as the Sovznak, could still be used to finance budget deficits, but would be saved from a final hyperinflationary collapse by a programme of austerity. Meanwhile, banks would begin lending to industry in the new ‘chervonets’, banknotes assigned a gold value equivalent to the Tsarist 10-rouble coin and given a hyperbolically retro graphic design intended to evoke pre-revolutionary commercial probity. Carefully protected from fiscal appetites and backed by gold, Sokolnikov proclaimed, the stable chervonets would open the way to a reanimation of domestic and international trade.

As I reach the late summer of 1923, the woods are changing. Ferns, it turns out, can grow remarkably high — sometimes I track Ziggy’s movements by the swaying of fronds nearly two metres from the ground, before he emerges doing his best impression of an Henri Rousseau tiger. The annoyingly spiky creeping plants forever tangling in the dog’s fur yield what I initially think are raspberries, though they later prove to be blackberries. In my aural Moscow, things are not going well. The collapse of confidence in the Sovznak has massively accelerated, far sooner than Sokolnikov expected, and despite huge new issues the total value in circulation has sunk by 40% in just two months. Because the chervonets note is far too valuable for most transactions, the Sovznak was meant to serve as small change, but its imploding value means there’s not enough for the purpose, leading to chaos and anguish in the shops and markets. Worst of all, chervonets-based prices are also rising rapidly, confounding the assumption that a gold-backed currency would be stable in value. Sokolnikov reacts by frantically moving the goalposts, changing monetary theory on the fly to clamp down on chervonets issue, and continuing to lay into his critics as knaves, fools, or both.

About a week before the not-raspberries appeared, my walks in the woods took on a new poignancy and intensity when I learned of the death of my teacher and friend Kiren Chaudhry. We had fallen out of touch, which feels inexcusable now. Without her, there’s little chance I would ever have made Sokolnikov’s acquaintance. Studying Soviet politics as an undergraduate, I had learned little and cared less about the country’s economy, in part due to my own short-sighted reluctance to engage with a topic deployed in US political debates as a symbol of statist decay against which the triumphs of Reaganite neoliberalism glowed even more brightly. But then in the spring of 1991 I took Kiren’s seminar in political economy, and my interests irrevocably changed. Just setting out as a junior professor, she was nonetheless possessed of a thoroughgoing irreverence and constitutional iconoclasm that offered a model of academic freedom. Her combustible impatience for cliched thinking and just plain missing the point provided the fuel for seminars that were as challenging as they were revelatory.

That spring, she stressed above all the profound historical amnesia involved in neoliberal talk of rolling back the state to unleash private initiative. For the market as we know it is a creation of the state. In the nearly three decades since, Karl Polanyi’s aphorism that ‘laissez-faire was planned’ has become ubiquitous. Kiren, though, was a pioneer in exploring the implications of the insight that the construction of states and the construction of markets are inseparable, at times indistinguishable processes fraught with massive political difficulties. A student of the Arabian peninsula, among many other places (in addition to the English, Punjabi, and Urdu she grew up with, she also acquired Arabic and Turkish), she was fascinated with the ways in which its would-be rulers failed or succeeded in channeling practices of exchange as they sought to extend their authority. Ibn Saud, for instance, had to contend with local preferences for a welter of foreign coins, such as the Maria Theresa thaler. (Kiren took some earthy enjoyment from the effect the Austrian monarch’s bosomy profile produced on the region’s merchants.) To standardise monetary use would integrate markets and facilitate taxation and spending, but would involve dislodging and angering merchant networks and add stresses to Riyadh’s relationship with different tribes and regions.

What Kiren could hear in such struggles, and what she challenged her students to hear, was something Schumpeter called ‘the thunder of world history’. For what other than a mighty rumble could be produced by the putting into place of structures grand enough to allow a state to create, sustain, tax and regulate a market economy, to shape our quotidian getting and spending, to open or foreclose commercial opportunities across a nation-state and beyond its borders, to constitute the very money and property whose lack or plentitude permeate our every experience? A recognition of the magnitude of these tasks led Kiren to argue that states assumed to have embraced statism for ideological reasons had often found their way to it as a result of frustrated efforts to build markets — -an argument she was ready to extend, provocatively but thrillingly for me, even to the Soviet Union. It was also an insight of some prophetic force, as the neoliberal hubris of the early 1990s gave way by the 2000s to a recognition of the complexity of markets’ institutional preconditions and hectoring efforts to instil ‘good governance’, little heeded by developing-world and post-Soviet governments lurching back towards alternatives to the Washington consensus.

As a graduate student, I saw Kiren as a virtuoso of the bulldozer, opening intellectual vistas I would otherwise have scraped hesitantly towards with a scalpel. (There was something about what Kiren had to teach that made extravagant metaphor seem the only way I could express it. Discussing with her the significance of financial globalisation while sitting beside the San Francisco Bay, I recall viscerally experiencing the currents of history playing across the waters and marvelling at our capacity to see to the other side.) I confess that for all my admiration, I’ve never been able to overcome my predilection for the scalpel, which may explain why I’m still visiting the 1920s after all this time.

By early 1924, Sokolnikov completes his currency reform, having suffered through a difficult autumn. Efforts to collect taxes from the peasants in money rather than grain collapse into farce as the value of Sovznak receipts evanesces before the state can spend them. Addressing the small-change problem by printing as many Sovznaks as needed just squeezes their value even further. They are retired at a derisory rate early in 1924, at which point Sokolnikov declares victory by celebrating the stability of the chervonets’ gold value.

This achievement was more curse than blessing. The gold value of the chervonets made the Soviet internal prices that emerged from the 1923–1924 maelstrom too high when converted to international ones, and over the course of the 1920s financial authorities were unable to find sustainable ways to bring domestic prices into line. This problem of currency ‘overvaluation’ was precisely the same as that decried by Keynes after Churchill restored the pound’s pre-war gold value in 1925. When Keynes visited Russia in September 1925, on honeymoon with the ballerina Lydia Lopokova, he met with Soviet financial officials and reiterated his critiques of Churchill’s error. (One of the fascinating aspects of the Bolsheviks’ monetary debates is just how very cosmopolitan they were. Pioneering US monetary theorist Irving Fisher, who argued like Keynes that price levels rather than gold values ought to drive monetary policy, did not exempt Bolshevik leaders from his relentless campaign of self-promoting letters. Sokolnikov reserved some of his most concentrated vitriol for Soviet advocates of Fisher’s approach, and scoffed to the Politburo that ‘no banker takes him seriously’ — well, I assume he scoffed, as Milena delivers the line straight. I can likewise only imagine the expressions on the faces of Bolshevik leaders asked to defer to the authority of capitalist financiers. Defer they did at the time, but this was Sokolnikov’s final Politburo meeting; in the 1930s he was a victim of the show trials.)

In Britain, employers’ attempts to drive down wages to offset the pound’s excessive gold value touched off the fizzled General Strike of 1926, memorably lampooned in Brideshead Revisted, where Charles Ryder and fellow toffs, kitted up with helmets and truncheons, are disappointed in their hopes of finding proletarians to beat into deference to international price ratios. But no one was joking in early 1928, when, faced with a shortage of grain for export, Stalin ominously enquired, ‘Who needs to be beaten to improve matters?’ and answered ‘those who speak about raising prices for grain’. A higher price, multiplied by the chervonets’ value, would price Soviet grain out of world markets and threaten the export receipts Stalin needed to fund industrialisation. Casually jettisoning Marxist theory to declare the countryside as a whole a hostile class, Stalin gave the signal for a campaign of violent coercion against the peasantry, which culminated in a catastrophic collectivisation of agriculture and a new famine that once again carried off millions of lives.

For me, that particular awful thunder of world history will sound in the future. This evening, Milena’s ventriloquist is Sokolnikov’s adviser Leonid Yurovskii, who, speaking from the pages of his history of the monetary reform, has taken me back to the waning days of 1922. I learn enough to infer the political background to Sokolnikov’s late-night appeal to Stalin over that price index, and also about the role of concern over spreading usage of foreign currency and old tsarist coins in motivating the push to introduce the chervonets. I take my headphones off and give myself over to admiring these new treasures, hefting my scalpel as I prepare to carve a setting for them in whatever it is I’m building in my mind. A fat rabbit makes an un-rabbity amble across the trail, but Ziggy ignores the implied insult to his wolfish amour propre. Ahead, under the leaves’ haphazard portico, the path Kiren cleared continues.

— David Woodruff, Reigate, Surrey UK, July 2020

In memory of Kiren Aziz Chaudhry, 17 March 1959–25 June 2020